AI and Surveillance at the Border – “The technology doesn't actually work at all”

10.09.2024Weizenbaum Distinguished Fellow Petra Molnar spoke to us about expensive border technology that does nothing but harm, and how we can bring back humanity into the conversation about migration.

In her new book, The Walls Have Eyes, lawyer and anthropologist Petra Molnar maps together a global story of border technology. We spoke to her about Western anxiety on migration, the dangers of her research and the technologies that migrants are using to cope with these regimes of exclusion.

What inspired you to write this book, The Walls Have Eyes?

Molnar: A happy accident. Eight years ago, I knew nothing about algorithms. Then in 2018, my colleague Lex Gill at the Citizen Lab and I discovered that the Canadian government was using experimental technology in the immigration system. We wrote a report that made its way around the world, which opened my eyes to the intersection of technology and migration. Since then, I’ve been trying to stitch together this global story, which culminated in my book, The Walls Have Eyes.

How do you go about your research in these dangerous areas around the border, and how do you actually get all this information for your book?

Molnar: I toggle between my role as a lawyer and my training as an anthropologist. I've always had a commitment to this ethnographic way of working.

For the purposes of being able to gather evidence and be present in these spaces, you sometimes have to go into areas that are designated to be a military zone, where researchers and lawyers and journalists aren’t allowed to be. The same goes for many refugee camps. A lot of the evidence in the book is actually from official visits. Other work had to be done in other ways because governments do not like too many critics poking their nose into these spaces. Not to mention the personal spyware and cybersecurity issues that come up when you're doing work that states don't necessarily want you to see, like the Pegasus and Predator scandal in Greece which happened while I was living there.

So, this type of work requires both preparation and experience. Initially, there's a fact-finding phase to identify hotspots. Often, it's an iterative process – spotting technology in use and going there to understand it better.

It's also a lot about building relationships, with civil society, journalists, and most importantly people on the move. This slower more grounded approach allows you to revisit spaces again and again and fill in the gaps in your understanding of the issue, opening up spaces for complexity.

What have you encountered in your research, what conditions and which technologies are migrants dealing with at the border?

Molnar: Technology virtually impacts every piece of a person’s migration journey. When they’re still in their home country, people are interacting with things like social media scraping that is used to build risk profiles on them. All this before you even move. Then at the border, or in spaces of humanitarian emergencies, that's where a lot of the sharp surveillance is happening: Drones, radars, cameras, biometrics – at the US-Mexico border, even robodogs. All very high risk, very untested and unregulated.

And then after the border, AI lie detectors, voice printing technology or visa triaging algorithms are used. It’s this panopticon of technology that follows a person as they are moving across borders and spaces

When did these high-tech border regimes first start out, and how have borders been changed by digital technologies?

Borders have always been violent spaces, and technology has always been part of that. Passports are a form of technology, and data collection dates back to colonialism when it was used to control and subjugate certain groups along racial and ethic lines. This usage of technology reflects a historical pattern of exclusion and violence. After 9/11, border digitalization and automation surged, and in the last decade, Western anxiety around migration has driven a rise in high-risk experimental projects. The U.S. introduced robodogs in 2022, and AI lie detectors were tested in Europe around the same time. Who knows what's next?

When you say high-risk technologies, what are those specific risks that migrants are confronted with?

Molnar: From a human rights perspective, it's the whole ambit of rights that are at risk of violation.

There are violations of privacy rights, for example. If data is being collected from people on the move and then shared with repressive governments – which has already happened – those are massive privacy breaches.

When it comes to equality and freedom from discrimination rights, we know that a lot of surveillance technology or face recognition technology is just blatantly discriminatory and racist. So, if we are relying on this type of technology to make determinations about extremely complex and sensitive contexts like refugee and immigration decision-making, it's really troubling that AI lie detectors are even being tested out at the border – which are themselves nothing more than snake oil.

Freedom of movement is another right that's impacted and the whole international refugee law framework, too - the foundational principle that every single person on the planet has the right to seek asylum. The principle of non-refoulement as well – not being returned back to a place where you are facing persecution. All of these rights are impacted by tech and surveillance.

Is this even legal?

Molnar: That's the open question. Right now, very little law actually exists to regulate technology generally, especially border technology. One could argue that most of this technology is not legal, but we don't even have a robust legal framework to pin that to.

The EU AI Act just entered into force on August 1st. And a lot of us were, perhaps naively, hopeful that this would be an opportunity to set a global precedent on regulating AI. But the text was really lacking the contextual specificity around border tech, or predictive policing and other high risk uses of AI.

A coalition of us, called Protect not Surveil, pushed for stronger policies to support people on the move, but political tensions around migration prevented the amendments. This failure at the EU level is disappointing and has global impacts. If the EU doesn't set a strong precedent, why would the US or Canada be motivated to regulate?

What do governments hope to gain from deploying these systems at the border? And is it actually working?

Molnar: States often say that these new technologies are for efficiency purposes. Efficiency is a strong argument to use. I used to practice refugee law in Canada. I know how inefficient the system is. It is long. It is opaque. It often just doesn't work. But a Band-Aid solution that creates other problems is not an answer to a broken system. This efficiency argument really doesn't get at the root issue, which ultimately is exclusion. You see this logic in policy documents, especially from Western states, this language of needing to keep people out, to “strengthen” borders. In this framing, people on the move are threats and frauds, and they must be kept away.

And the interesting thing is, increasing surveillance and border tech is not keeping people away. Instead, people are taking more dangerous routes because they are desperate. They're not going to stop coming. And that's actually leading to loss of life, both at the US-Mexico border, but also in the Mediterranean or Aegean Sea. I've been working in migrant justice since 2008 and on this book since 2018, and I've spoken with hundreds of people on the move – we often forget that people don't want to be refugees. But when you are desperate to save your family, you will do whatever you can to make that happen.

Another point is, that the technology often doesn't actually work. I’ve seen this in Greece, there were plans for AI and virtual reality glasses for border guards, along with drones, and biometrics. But as theorists like Martina Tazzioli remind us, it’s not totally clear what this technology is actually doing on the ground. It's a kind of performance, this theater of surveillance – also for political gains.

-

© Petra MolnarSidero graveyard for people who have died crossing into Europe, Evros, Greece.

-

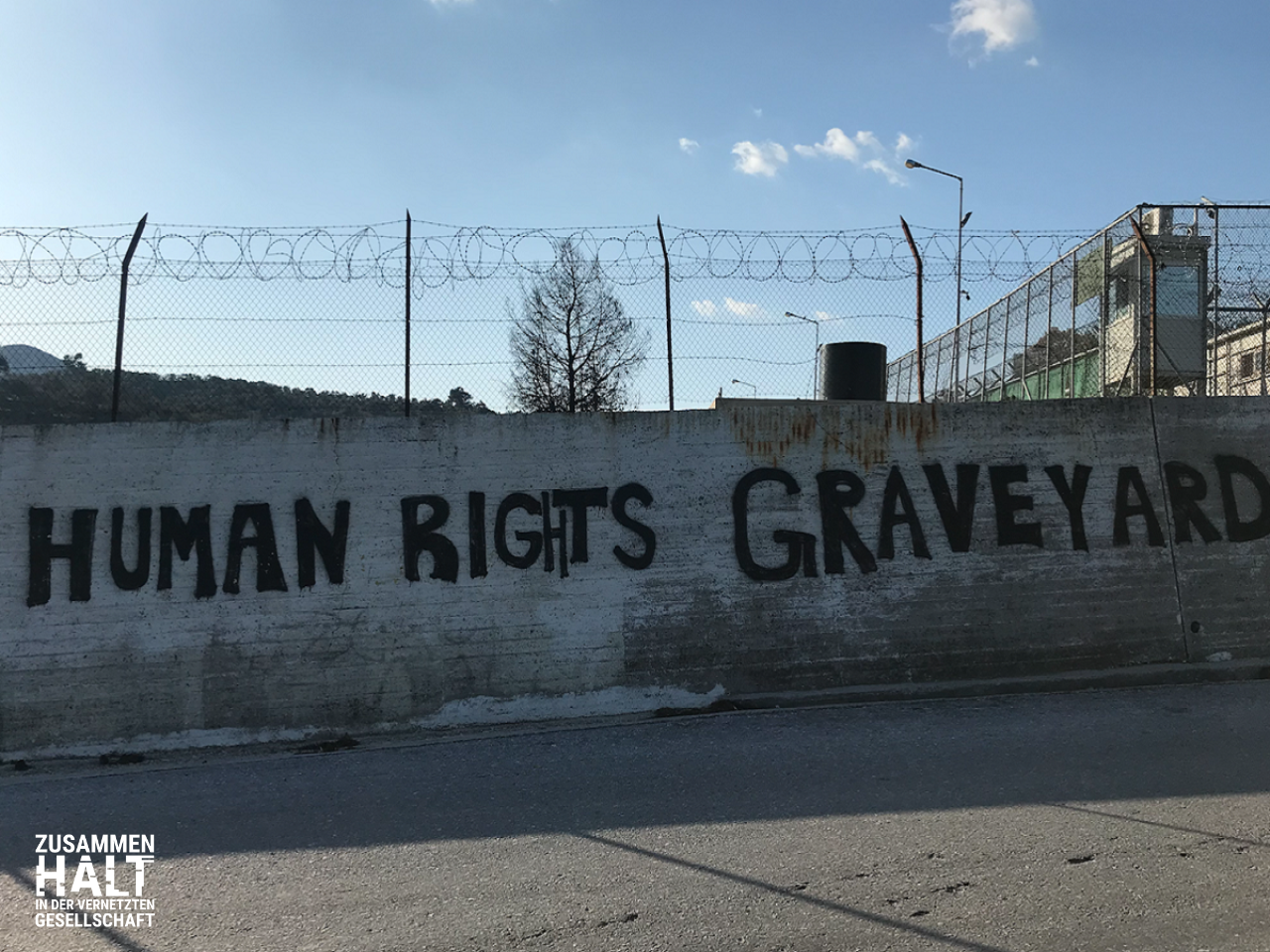

© Petra MolnarProtest against Samos Camp.

Do you have an answer how migration could be regulated in a better way?

Molnar: It’s ultimately a question about where resources are actually being spent and how much money is being dumped into border tech. The estimated figure is around $70 billion in this border industrial complex. Imagine if we spent just a fraction of that on housing, on legal support, on language training, as well as addressing the root causes of displacement so that people don't even have to leave their homes in the first place unless they choose to.

We are weaponizing this technology against people who are on the margins because that is the kind of norm that has been established by the powerful actors around exclusive tables where innovation and policymaking happens.

Who is part of this border tech industry?

Molnar: All kinds of companies, the classic ones like Palantir, Israel’s Elbit Systems, or Clearview AI, with very dubious human rights records. They're the ones who are getting the big contracts. Then there are huge multinational companies. In the European context, Thalys comes to mind, or Airbus. But there are also a lot of smaller companies too, that a lot of us have just never even heard of. And then there are some surprises too! The company behind the Roomba vacuums are also in border tech, for example (something which I am exploring in my upcoming second book)

This proliferation of actors also maps on to the geopolitics of tech development – a kind of AI “arms race,” some people have called it. You have these major players like Israel, China, the US, or Europe clamoring to be the leader in AI development without a lot of law to put some guardrails around this.

How big is the industry’s influence on policy decisions?

Molnar: States are motivated by these logics of exclusion, but they often can't develop the technology they want in-house themselves. That’s why they need the private sector. So, when companies claim to have this technical solution to the “problem” of migration – and that's drones, robodogs, or AI – then that sets the agenda in terms of what we innovate on and why. We could be using AI to audit immigration judges, for example, or root out racism at the border. But that's not what is being done.

A lot of it has to do with politics. Migration has become this politically fraught topic and also defining election issue for a lot of governments to say they take a strong stance on controlling (or stopping) migration.

What role does academia play?

Molnar: Academia has a big role to play here in legitimizing the way that technology is developed. For example, the project iBorderControl – a Horizon 2020 pilot project – was developed in partnership with a UK University. This project, billed as an AI-lie detector for the border that would use facial recognition and micro-expression analysis on travellers, generated a lot of criticism and MEP Patrick Breyer even started a compaant with the EU Court of Justice. Projects like this one are extremely inappropriateand discriminatory – nor does it even work. What these partnerships also highlight, however, is this hubris of academia thinking that we are the experts, and then using that framing to legitimize these extremely problematic projects. As someone who works in academia, I think this really needs to be questioned. The same goes for research funding. A lot of it is funded by military companies and other problematic actors in the tech space. I think we actually need open and public conversations about how academics are getting funded and what kind of donors they have to placate with the research that they're doing.

How are migrants coping with these surveillance regimes? What kind of technologies are they using, and what are the forms of resistance and solidarity?

Molnar: There's always resistance and solidarity, and it’s in some really unique and creative ways that people are co-opting or using technology. One that immediately comes to mind is TikTok. People on the move are using “MigrantTok”, to share videos of their journeys and experiences.

But there are also projects that are being developed for and by mobile communities as well, for example, chatbots are being designed by refugees for refugees like work being done by my colleagues Grace Gichanga (South Africa) and Nery Santaella (Venezuela), different types of psychosocial support technology, or archival memory technology, like MTM’s Simon Drotti (Uganda). These are some of the projects that we incubate at the Migration Technology Monitor project. Another of the projects is called The Memory Scroll by my colleague Simon Drotti (Uganda). It's a psychosocial online archive and a platform for people on the move, to tell their own stories on their movement.

So, there are definitely ways that technology can benefit mobile communities. The human rights space is moving more towards the direction of working together, to highlight what the reality is on the ground and then to see what we can do about it.

What are the political and legal strategies to challenge this tech violence at the border?

Molnar: Legally speaking, it is difficult when you don't have a lot of law on which pin responsibility. Some of us have been trying to use international refugee law, international human rights law, and sometimes domestic privacy legislation. And our team at the Refugee Law Lab is thinking about strategic litigation in the future. We’re trying to identify different avenues, for example to get either a moratorium or an outright ban on high risk border technologoes – or find ways to hold entities like Frontex, the European Union's border force, accountable for the tech that they're using for pushbacks and the like.

Politically speaking, it's also about nuanced storytelling Sometimes, my own work gets criticism for not being hard science, I’m told it’s too qualitative and too story driven. But ultimately, it’s about making space for people on the move to tell their own stories and getting them out there in front of policymakers to bring some humanity back into the conversation.

And that's also something that we're trying to change with the way we work at the Migration and Tech Monitor. Because it's about these broader questions of who counts as an expert. Why is my colleague on the move any less of an expert than some academic who's never left their office? People on the move are the ones who are living this reality – every day.

Thank you for the interview!

Dr. Petra Molnar is a lawyer and anthropologist specializing in technology, migration, and human rights. Petra has worked all over the world including Kenya, Palestine, Jordan, Turkey, Philippines, Colombia, Canada, and various parts of Europe. She is the co-creator of the Migration and Technology Monitor, a collective of civil society, journalists, academics, and filmmakers interrogating technological experiments on people crossing borders. She is also the Associate Director of the Refugee Law Lab at York University and a Faculty Associate at the Berkman Klein Center for Critical Internet at Harvard University. Petra’s first book is called The Walls Have Eyes: Surviving Migration in the Age of Artificial Intelligence (The New Press, 2024).

She is a Distinguished Fellow at the Weizenbaum Institute from June to September 2024.

She was interviewed by Katharina Stefes and Leonie Dorn

More on the topic

The Migration and Technology Monitor Project: https://www.migrationtechmonitor.com/

The Walls Have Eyes companion side – The Lawyer’s Notebook: https://www.petramolnar.com/the-walls-have-eyes

Op-Ed, Time Magazine: https://time.com/6979557/unregulated-border-technology-migration-essay/

---

This interview is part of a special focus "Solidarity in the Networked Society." Scientists from the Weizenbaum Institute provide insights into their research on various aspects of digital democracy and digital participation through interviews, reports, and dossiers.

More at: https://www.weizenbaum-institut.de/en/solidarity-in-the-networked-society/