Does copyright still matter in the Age of AI?

08/20/2025We spoke with Weizenbaum researcher and legal expert Zachary Cooper about whether copyright still has a future, and if struggling creatives can rely on laws to help them against the economic precarity made more severe by generative technologies.

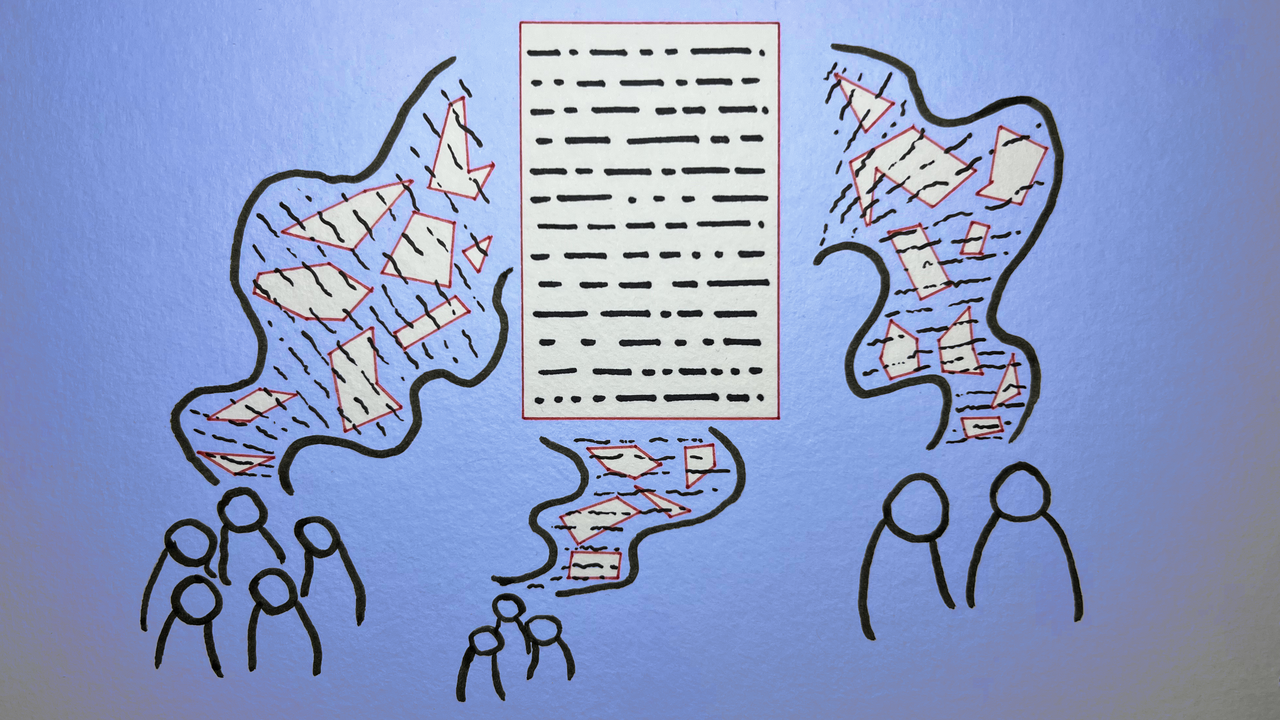

The rise of Large Language Models and image generators has sparked major questions and disruptions regarding intellectual property and copyright. The hype around the new technology has been met with controversy as it became increasingly clear the models were trained on the work of authors, journalists, and musicians without compensation. Earlier this year, when Open AI’s image generator was used to create countless images in the distinctive style of the acclaimed Studio Ghibli, it sparked outrage and raised serious concern about the legality of such practices.

As the first court rulings slowly emerge to determine which uses of generative AI tools constitute copyright infringement and what is considered "fair game," we sought out Weizenbaum Fellow Zachary Cooper— a legal expert, researcher, and artist—to discuss the future of copyright. We explore whether existing laws can provide economic security for creatives in this new age of AI and digital platforms.

First of all, can you tell us about your research focus, and what you are currently working on?

Zachary Cooper: Well, it is worth noting, that I’m a lawyer but I’m also an artist - a musician mostly, but also a filmmaker. I’m looking at the effects of generative AI on new forms of creativity, how AI is about to shift how we produce, consume, and disseminate creativity, and how that intersects with intellectual property. I’m currently exploring what happens once AI reaches high levels of speed and control—when you can instantly change a song or artwork just by directing it. How should we recreate rights around that? Should we be allowed to do it? And who should get the money when things are changed?

Copyright is a heavily debated issue right now. There was a large controversy concerning Studio Ghibli at the beginning of this year, and the head of the U.S. copyright office was fired recently over conflicts around AI. Can you explain what the different sides are arguing about?

ZC: People are really passionate about copyright. Trump doesn’t want copyright to get in the way of training models in the “AI Race”. At the same time, it’s a very economically insecure moment for many industries now – creatives, journalists. It always has been for creatives, but generative AI has made it even more insecure. I think there's real fear that these technologies will remove the last spaces where creatives can make money.

Not that long ago, it was much more common to hear from people who were really against copyright. Mashup artists embraced repurposing each other’s work—and that was considered a major part of the creative process. Copyright was criticized as a tool used by major rightsholders—major labels or studios—to stop people from being creative. In the case of sampling, people felt it was destroying hip hop. Certain lawsuits actually did change the sound of hip hop, which went from being really sample-heavy to using re-recordings. Now, with AI, a lot of artists are very pro-copyright again.

What’s interesting is the broader moral backlash against AI, mixed with creatives feeling insecure about their economic situation. When we look at cases like the Studio Ghibli example, I think it’s important to ask: What are we really angry about? Are we upset that something can be made in the style of another artist—is that truly an affront? Or are we actually angry about the economic instability creatives are facing today? That’s important, because simply arguing for more copyright doesn’t necessarily save creatives from the economic precarity we’re currently experiencing. The AI models that may be able to replace certain creative work don’t disappear if there’s stronger copyright protection, nor is there necessarily a big paycheck waiting for artists if AI companies need to pay for training data.

It is currently still debated whether something generated by AI actually violates copyright. Why is this so hard to determine?

ZC: With AI and copyright, there are two stages where there may be copyright infringement issues: the training of the model, and then the model outputs.

With companies like OpenAI, we don’t know always know how their models are trained; it's confidential. Studio Ghibli is so classic, with so much fan art and similar content online, you might not even need to train on protected material to output in its style. It’s also hard to track where your work ends up online and the Internet is not always well-labelled, so even if you scrape huge amounts of ostensibly public domain space, there may actually be protected materials in there.

As for the output, it’s also fraught. If you ask for something in the style of Studio Ghibli, that’s not usually considered copyright infringement. It’s important that we allow style imitation—otherwise, Chuck Berry might own all of rock and roll and no one could make a rock song. Genres and styles need to remain open. Still, is this more problematic now that Chuck Berry doesn’t get paid to create something because a machine can be asked for something in his style? Again, though – is this a copyright question? Or a labour question?

It gets more complex with generative AI when it touches on persona—using voices or representations of real people. At what point is it style, and at what point is it persona? If a voice sounds like Taylor Swift but doesn’t represent itself to be Taylor Swift, should she own that? There are other people with voices like Taylor Swift. Does she own all voices that sound like her?

On top of that, if a generative AI tool produces a copyright-infringing image, should you as the user really be liable? You may never have even seen the image you’ve replicated. Should the AI company be liable? They might also have gone to some lengths to try to make sure that the models don’t spit out infringing images.

It’s all still up in the air—we don’t have case law yet to answer it.

Yet, it is pretty safe to assume that generative AI has been trained by the body of work of authors, journalists, musicians. So far, they haven't received compensation. It seems like current copyright laws have failed to protect them, why is that?

ZC: What’s happening with LLM training isn’t clearly or obviously copying in the conventional sense. All this content is scraped from the internet and converted into weird vectors and probabilities—a black-box that can now determine how likely something is to follow something else. That’s not the same as copying a picture and turning it into another picture.

When web scraping first became an issue, the context was fundamentally different. It was Web 2.0—Google was scraping data to build useful indices to help people navigate the internet. With robots.txt, sites can decide whether they want to be scraped or not. Most sites wanted their content scraped so Google would link to it. When the legal questions first came up, U.S. judges found caching by Google in a number of instances to be substantially transformative and therefore fair. Now, these models are being trained, and the concern is that what they can do competes with what’s already been created.

Copyright law is complicated and open to reinterpretation in different circumstances. It remains unclear when the violation is actually happening: Is it the scraping, or what’s then done with the scraped data? That’s what’s being fought out in court right now.

Big publishers like the New York Times now have licensing agreements with AI companies that allow them to scrape their content, will this make a difference?

ZC: It makes a big difference. On the one hand, it’s good – nobody wants AI to destroy journalism, so economic models need to be worked out such that it still receives funding if people start getting all of their news from LLMs. On the other hand, there is a risk to these deals that they create a homogeny of content, since then models refer to limited or selected sources. It can also raise democratic concerns if the biggest bidder influences LLM outputs – so there are power dynamics to consider there.

In other industries, it is not certain that licensing agreements resolve their precarity. AI companies can’t license everyone’s work individually – so they turn to major rightsholders. We saw a similar dynamic during the advent of Spotify and other streaming platforms—they made deals with the three major labels.

But as with streaming, that didn’t mean that the deals led to every artist getting paid well for their work. In that instance, the labels negotiated for equity in the streaming platforms, rather than higher payouts for their artists. And in the models trained up until now, it may be difficult to determine how much any individual piece of content was used in training, rather than simply counting streams – so it’s not yet clear what that payout model would be.

Creatives use AI for their own work. A recent decision by the U.S. Copyright Office stated that if the work contained enough human creativity, it would be eligible for copyright. You and our colleague Volker Stocker criticized this decision. Why?

ZC: Well, the report differentiated copyright for when AI is simply a tool versus “purely AI-generated” works. The problem is, neither of those categories are robustly defined. There’s no clear way to tell what counts as an AI work or not. “AI” is a meaningless signifier, it just means software, we're talking about buttons in a creative workstation.

Judges and the Copyright Office are now trying to separate works into copyrightable and non-copyrightable parts based on which elements were made with generative AI. In theory, it sounds reasonable; in reality, it’s created total confusion. Now we don’t even know which parts of a song, artwork, or video are protected unless we know exactly how it was created, click-by-click. That has led to a whole industry around so-called “AI watermarking” tools—meant to track when AI is used. They’re not only unproven to actually work - once you rely on these tech solutions, you just create a new industry for people to break them. It becomes a hacker vs. hacker game: watermark, decoder, new watermark, new decoder. Plus, for them to really work, you need to track an artist’s entire creative process. So it’s inherently surveillant.

Is this the end of copyright as we know it?

ZC: Copyright is very valuable, so it’s not going anywhere any time soon. The question is its relationship to how we create in the future. And that is different across media—because each has its own market dynamics. Copyright may be super valuable in one market and not as helpful in another.

As creative economies have become more platform-based and social media content especially is more focused on building brand value, the content itself can become an ad for creators to earn money elsewhere. For example, many musicians I know consider streaming more like an ad to sell records or tickets to their show, due to such low streaming payouts. But if your work is most lucrative as an ad to recoup value elsewhere, copyright isn’t as relevant — then you want your content to proliferate across social media as much as possible. You don’t want to control it. There would be no “Brat Summer” without mass remixing and repurposing across TikTok. So when Universal pulled all its music from TikTok last year because they thought TikTok wasn’t paying enough royalties for it, some of their signed artists got really angry because they couldn’t promote their album on there. Apparently, Olivia Rodrigo promoted her record with sped-up versions of her songs that got past TikTok’s content filters. It’s more important to have your work on there and not really get paid for it, rather than not having it on there at all.

Now things are changing, because once generative AI gets fast enough and controlled enough—which I think could be very soon—we’ll enter a phase where all media can become interactive. That fundamentally shifts creativity, blurring the line between artist and audience, since the audience can now redirect the art they consume.

My fear is that copyright will drive this new mode of creation and consumption even more into the hands of big platforms, because they can clear the rights for people to do this to all the content that is uploaded there. That type of instant-remixing would still be inherently violating copyright, unless you’re doing it within a walled garden like TikTok that can set its own terms and clear all the rights to everything on there. But as platforms control more media, copyright might become less valuable because then the platforms have more negotiating power. If no one's going to consume your work outside of these platforms, then you have no option but to license it out on their terms unless you’re powerful enough to renegotiate them.

Will this have an effect on the art that is created?

ZC: Yes, certainly. What I fear is a proliferation of meme-ified music and art. I think as that line between audience and artist is blurred, and everyone can create their own version of things very quickly, creators might focus on making media that invites others to put their spin on it so that it’s more likely to go viral. Rather than trying to create the perfect song, you're trying to create the best hook – something that is most engaging across genres or that invites millions of versions.

If copyright is not the answer – what helps creatives in the digital age trying to compete with AI?

ZC: I think one of the big problems with certain creative industries is that people aren't paying enough directly to artists for their work. Doing that is much easier than trying to figure out hyper-sophisticated algorithms tracking everything and paying out everyone accordingly.

I think artists should try to create their own models and networks that allow for more direct relations with their audiences, and reject those platforms or networks that don’t serve them. We don't need the law to say which art is valuable and which isn't, nor to divvy up rights based on creative processes. We just need individuals to support the economies that they're interested in, even where it’s at the expense of efficiency and convenience. Otherwise, we’ll all end up having fabulously cheap, efficient and convenient access to junk.

Thank you for the conversation.

Zachary Cooper is a legal scholar, researcher and lecturer for the Amsterdam Law & Technology Institute of the Vrije Universiteit Amsterdam. He has written and taught courses for the Vrije Universiteit Amasterdam in The Law and Ethics of Robots & Artificial Intelligence, Blockchain and Other Disruptive Business-tech Challenges to the Law, Multinationals and the Platform Economy, & Data Analytics and Privacy, and is currently co-editor of the European Journal of Law & Technology.

Interview by Leonie Dorn

artificial&intelligent? is a series of interviews and articles on the latest applications of generative language models and image generators. Researchers at the Weizenbaum Institute discuss the societal impacts of these tools, add current studies and research findings to the debate, and contextualize widely discussed fears and expectations. In the spirit of Joseph Weizenbaum, the concept of "Artificial Intelligence," is also called into question, unraveling the supposed omnipotence and authority of these systems. The AI pioneer and critic, who developed one of the first chatbots, is the namesake of our Institute.